Palestinians, both at home and abroad, have found an unlikely partner in the struggle against colonization: First Nations, the indigenous peoples of Canada.

By Hadani Ditmars

Native peoples from all over the world joined together on Monday as part of an international day of solidarity with Idle No More, an indigenous uprising that has supporters across the globe.

Idle No More began in Canada, but it has sparked support from peoples including North African Tuaregs and New Zealand Maoris.

And with the many messages of support that came on Monday from indigenous peoples across the globe were messages of solidarity with Palestinians - both in their historic homeland and flung throughout the diaspora.

On the homepage of the Canada Palestine Association (CPA) is a link proclaiming "Palestinians in Solidarity with Idle No More and Indigenous Rights."

It opens with an excerpt from the Mahmoud Darwish poem, "The Last Speech of the 'Red Indian' to the White Man":

"You who come from beyond the sea, bent on war,

don't cut down the tree of our names,

don't gallop your flaming horses across

the open plains ...

Don't bury your God

in books that back up your claim of

your land over our land ..."

The message's signatories declare themselves both Canadian and Palestinian and standing in solidarity with Idle No More.

They include the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network; the One Democratic State Group in Gaza; the U.S. Palestinian Community Network and dozens of individuals, from Toronto to Ramallah.

Canadian aboriginals are also known as First Nations. And while solidarity between Palestinians and First Nations has existed for decades, says Toronto-based Canadian native poet and activist Lee Maracle, Idle No More has "crystallized" the relationship.

"The links between peoples are clearer," she says. "We'reboth colonized. They're after our resources in the North," she says, citing the controversial tar sands bitumen extraction projects in Alberta, "and land and resources in the Middle East."

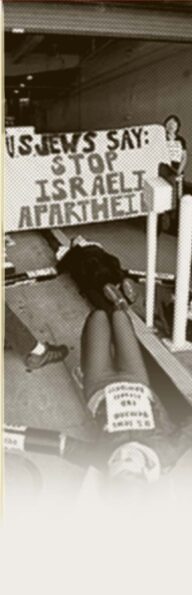

Maracle and her family have been working side by side with Palestinian activists for years. During Operation Pillar of Defense last year,her daughter, Columpa Bobb, took documentary photos of young native activists in Winnipeg, who joined with Palestinian-Canadians and others in protest.

Maracle remembers meeting Mahmoud Darwish at a public reading in Vancouver in 1976 to welcome the Palestinian delegation attending the UN Habitat conference on human settlement. There, she read his poetry in English, and he read it in Arabic.

Hearing his work, she says she felt an intrinsic connection."He spoke to something so old inside my body it felt like floating in a sea of forever," Bopp says.

In 2006, when Assembly of First Nations Chief Phil Fontaine accepted a paid visit to Israel from the Canadian Jewish Congress, she wrote a letter to the AFN, saying, "This is tantamount to laying a wreath at [South African leader John] Vorster's grave in the interest of [honoring apartheid] or traveling to the U.S. to share the values of the Custer Committee celebrating the massacre at Wounded Knee [an 1890 massacre of Indians by the U.S. cavalry in South Dakota]."

AFN's Israel visit underscored a sort of battle of dueling narratives, with right-wing Zionist groups trying to claim kinship with First Nations on the grounds that both were "aboriginal" peoples.

Furthermore, the indigenous issue in North America has been used by former Israeli prime ministers like Ariel Sharon to justify occupation and settlements in Palestine - throwing it in the face of those who criticized Israeli treatment of Palestinians.

"We have learned a lot from you Americans, how you moved West," Sharon once remarked to a U.S. official. Many have compared have compared Gaza to a large American Indian reservation.

Many activists, however, beg to differ.

In fact, says Hanna Kawas, a Palestinian-Canadian journalist and longtime activist for indigenous struggles both in Canada and the Middle East, "The Zionist movement was also built on the South Africa, Zimbabwe, Angola, Guinea Bissau, Mozambique, Algeria and other European settler-colonialist models of the same era," and as such, should not be supported by indigenous peoples in Canada.

Kawas, who lives near Vancouver, has attended Idle No More protests over the past several weeks but emphasizes that, "While we're[indigenous Canadians and Palestinians] not hiding our support for each other,we're [Palestinians] not trying to further our own agenda - but rather to advance theirs."

Kawas' support for indigenous rights stretches back to the 70s, when he first arrived in Canada (his family were refugees from Bethlehem). He remembers First Nations activists coming out to protest a 1975 visit to Vancouver by Moshe Dayan, and also took part in many protests to free American Indian Movement activist Leonard Peltier, who was extradited from Canada at the request of the FBI. Peltier is still in a U.S. prison.

He also describes a meeting that the Canada Palestine Association had with a First Nations group of female elders. That happened in Vancouver in 2006, when the groups gathered to speak about then AFN head Chief Phil Fontaine's visit to Israel.

Fontaine, Peltier says, is "a first Nations Abbas," referring to Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. "He's part of a corrupt leadership that does not represent the grassroots."

"The elders invited us to speak about our position and agreed with us. After the meeting they gave us a special eagle feather as a present - which I consider my visa and my passport to this land," he said.

For 34-year-old Vancouverite Mike Krebs, a student of political geography who has indigenous Blackfoot ancestry, the connection between the Palestinian and indigenous Canadian struggle is a "natural one."

Krebs met his extended Blackfoot family, who still live on a reserve in rural Alberta, the same year that the second Palestinian intifada began. That was a coincidence, he says, that gave fuel to his activism.

He remembers attending a talk in Vancouver by Israeli human rights activist Jeff Halper in 2001.

"He showed us a slide of different maps of Palestine - one from pre-'47, one from '48, '67 and 2000 - and that's when the connection clicked for me, this image of a shrinking land," Krebs says.

In Vancouver, Krebs collaborated with Palestinian activist and academic Dana Olwan to produce an article for an Australian journal called "Settler Colonial Studies," comparing Canada and Israel. "We were just naturally interested in each other's struggles," he says.

But there are important differences, he notes.

"Palestinians have far less mobility than indigenous Canadians and face daily IDF assaults and frequent attacks from settlers, but have not lost their language, as many First Nations have. And the scale of genocide is greater amongst First Nations who saw their populations decimated."

Comparisons can also be exploited by right-wing pundits who have demonized both First Nations and Palestinian activists as "terrorists."

But the real commonality lies in the land.

"Both peoples have a deep sense of relationship to and responsibility for the land," says Krebs. "And when that land is taken away, it destroys the culture."

Citing Ben-Gurion's 1948 statement, "The old will die and the young will forget," Krebs says the assumption from both Canadian and Israeli authorities was that both peoples would die off or assimilate.

"Well we haven't all died, or gone away. We're still here and getting stronger. There's a political and cultural revitalization going on that neither Canada nor Israel might have expected or wanted," he says.

Hadani Ditmars' ancestors fled Lebanon a century ago for Canada, where they were adopted by a Haida Indian chief. She is the author of "Dancing in the No-Fly Zone: a Woman's Journey Through Iraq," and belongs to the Eagle Clan.

URL: