California to Palestine: Fasting in Solidarity | Other VoicesOctober 10th, 2011 by Gabriel M Schivone

IlanaRossoff is a daycare worker by day and political organizer by night. She recently graduated from Hampshire College, where she studied US History, race studies, and Jewish studies, and completed a senior thesison the history of Jewish anti-Zionism (mostly) in the US. At Hampshire,was active in Students for Justice in Palestine, Student for the Freedom to Unionize, and White Anti-Racism Folks, at one time or another. She has also been active as a student organizer in the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network for over two years. She currently lives in Morristown, NJ, where she is slowly thinking about how to shake things up, and is always looking for accomplices.

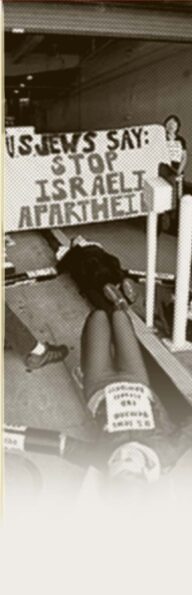

SCHIVONE: Talk about Friday night’s protest at the Wall Street Occupation. Why did IJAN want to organize this gathering, and why on the most solemn and important of Jewish holidays?

ROSSOFF: I helped to organize a contingent of people to be at Occupy Wall Street in New York City as part of a national and global campaign to bring together issues of profit-driven mass incarceration, political repression, and prisoners’ rights in the US and Palestine – geographically-separated but intertwined struggles. This past week, the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network (IJAN) had put out a call for actions to be held in three cities, to demonstrate (in some form) in solidarity with the prisoners on hunger strike in Palestine and in California. A couple weeks ago the Campaign to Free Ahmad Sa’adat (a longtime leader in Palestinian political resistance) put out a call for widespread global demonstrations. This was to highlight the indefinite hunger strike initiated on September 27 by many Palestinian political prisoners, specifically demanding an end to prisoner isolation and humiliation during location transfers. At the same time, on Sept. 26, the prisoners at Pelican Bay State Prison in California announced they were resuming their hunger strike, which they started and ended this past July after negotiations began with the prison administrationover their demands for better conditions for themselves and visitors. We wanted to bring attention to both hunger strikes, and recognized the importance of connecting the issues of political and racist incarceration of Palestinians and racist, politically-motivated mass incarceration, disproportionately of people of color, in the US. Yom Kippur was very timely, in this sense. Yom Kippur is said to be the mostimportant Jewish holiday, as Jews take seriously the wrongs we have committed against other people, ourselves, and the world at large, and ask for forgiveness. In doing so, we promise that we will actively seek out those whom we have wronged and do things to make it right with them.

At this moment in history, American Jewish communities bear an particular collective responsibility for atonement and action. Whether or not it is acknowledged explicitly, the silence of the overwhelming majority of Jewish communities about the expanding Israeli occupation and general racism towards Palestinians in Israel and the diaspora is always with us. Injustices against Palestinians are carried out in the name of Jews globally, whether or not we agree, and unless we confront them directly, these injustices are allowed to speak for us. Thus, there is a dual injustice and a dual responsibility – both to prevent itfrom continuing and to actively oppose its speaking for us. On this year’s Yom Kippur, it felt timely and meaningful to extend the usual 24-hour fast into a 48-hour solidarity fast. Not only did that give it greater significance to me personally, but it transformed the traditionof fasting into something both collective and immediate, very powerful qualities for spiritual practice and political work.

How was it physically for you to fast? Was it a struggle, so to speak?

Physically, it was only hard on the last leg of the second day. The first day was easy because I was energized for the action in New York City, and then totally distracted by it. Also, fasting for one day is not so hard for me because I normally fast for one day on Yom Kippur every year. But sitting in temple all day on Saturday became pretty brutal, not having fasted for that long before just sitting mostly in one place singing beautiful songs while debating their meaning to me from about 12:00pm to 6:30pm … what I’m getting at is that it wasn’t pleasant. But I got through it, as I knew I would. Thinking about the hunger strikes and the global solidarity campaign really inspired me andgave me the motivation to stick it through to the end.

There was a political purpose behind the fast, and it affected you physically. In that sense, the fast was at once personal and political. Is that accurate?

Yes. I think that phrase has a different meaning, though; that the systems of control and domination that we understand to operate on a large scale in society affect our everyday living and ways of being (a concept mostly introduced to the feminist movement by radical feminists of color in the 70s and 80s). But on the same token, our bodies do not exist in a different world than these politics, and being in solidarity with a hunger strike 5,500 (and 3,000) miles away literally means not eating (or drinking much) for two whole days. It takes a degree of privileged separation not to understand fully how the political structures of our world physically impact us day to day. You already know that if you, say, can’t visit your family member across a border 20miles away, or rely on international agency-provided food and shelter. So yes, it was affected me personally, but in different ways than it would others.

This fast was definitely more meaningful for me because there was an applied context and it meant something beyond just myself. As I said earlier though, it was not just about how it made me feel in my personal, spiritual practice, but had genuine significance as a part of an international effort of solidarity with political prisoners. While I physically felt the lack of food and hydration of the fast, I was alwaysaware that it was not really about relating to the experiences of thosein prisons, because it was not possible to. Those on hunger strikes from within prisons are choosing to stop eating or drinking for an undetermined period of time, in a facility where they already have little control of what happens to their bodies, with the hopes that the administrators or politicians will care enough to notice and negotiate with them, unless public outrage forces them to first. It is a precarious last resort, utilizing one of the only things they still havecontrol over – all the more reason to raise hell on our end to make it known that they are putting themselves on the line for better and more just conditions for themselves and others.

Talk a bit more about IJAN. Describe yourselves as an organization of individuals – what are your goals and principles, in a nutshell?

IJAN is a really powerful group of people and I’m really excited to be a part of it as it continues to shape its role and work within the Palestine solidarity movement. I came into IJAN the summer after my first year at Hampshire College, which was the first year I started doing Palestine solidarity work, after encountering some IJAN organizersat the White Privilege Conference in Memphis at the “Zionism = Racism” workshop they put on. In all of my confusion about the seeming conflictsbetween what I had been taught was part of my Jewish identity and beingopposed to the Israeli occupation, working through all of the emotionalattachments to Israeli exceptionalism engrained in my me by so many Jewish institutions, IJAN brought a rea

lly clear analysis of the role that Zionism plays in the displacement and exclusion of Palestinians, the racism inherent to the idea of a Jewish-dominant or exclusivist state, and in the interests of American Zionist or “pro-Israel” organizations. Today, IJAN is strong in Chicago, the Bay Area, the Twin Cities, England, France, Spain; and present in Atlanta, Los Angeles, NewYork, Geneva, Argentina, Morocco and a few other places. While the bulkof its work is concentrated in the US at the moment, IJAN’s scope is international because it understands Zionism to be the root international force which drives, supports, and justifies the ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. The organization is very principled, and positions its opposition to Zionism within a broader framework of opposing colonialism, imperialism, and racism, as well as gender and sexual oppression, in all forms – understanding the role that Zionism plays in services of Western imperialism and racism, how Western imperialism reinforces Zionism, and at the same time how Zionism relies on its own forms of imperialism and racism. IJAN also asserts its own, independent stake against Zionism as an organization of Jewish people. Because Zionism claims and monopolizes all of Jewish history and culture in order to garner support for the colonization of Palestinian land and culture, it erases the multiplicities of Jewish history and culture, particularly anti-Zionist and anti-capitalist histories. Thus, IJAN asserts, Jews have a stake in the movement to decolonize Palestine,as our histories and futures are entangled in it. What really resonateswith me about being a member of IJAN is that it places me in the movement with a clear position to oppose that which is done in my name, but not because there is something inherently valuable about a Jewish voice on the issue of Zionism. In fact, we reject that idea, which privileges Jewish voices and ideas over those of Palestinians; rather, we believe that because of our position of political privilege as Jews, which gives us more legitimacy on the issue, we must be vocal to oppose the injustices committed in our name and directly confront that which speaks for us.

I know that while a lot of people of my generation are coming to disassociate themselves from Israel and even Zionism, not everyone is doing it in such an explicit or confrontational manner. I wouldn’t suggest that everyone should come and join IJAN immediately (unless you’re really moved to!), but I would encourage anyone second guessing the myths of Zionism that they were raised with to go further than that:investigate the realities of Palestinian life and history under occupation, and begin to think about how you can make a meaningful contribution to their struggle for justice and freedom. The longer we remain silent, the longer others speak for us in the name of injustice.

Gabriel Matthew Schivone is a Chicano-Jewish American, founder of Jewish Voice for Peace at the University of Arizonaand co-founder of UA Students for Justice in Palestine. He is also a volunteer with migrant justice organization No More Deaths/No Más Muertes. He currently attends Arizona State University and can be followed on Twitter via @GSchivone. His column, Other Voices, appears here on alternating Mondays.