It's hard to imagine now,but in 1944, six years after Kristallnacht, Lessing J. Rosenwald, president ofthe American Council for Judaism, felt comfortable equating the Zionist idealof Jewish statehood with "the concept of a racial state -- the Hitlerianconcept." For most of the last century, a principled opposition to Zionismwas a mainstream stance within American Judaism.

Even after the foundation of Israel,anti-Zionism was not a particularly heretical position. Assimilated Reform Jewslike Rosenwald believed that Judaism should remain a matter of religious ratherthan political allegiance; the ultra-Orthodox saw Jewish statehood as animpious attempt to "push the hand of God"; and Marxist Jews -- mygrandparents among them -- tended to see Zionism, and all nationalisms, as adistraction from the more essential struggle between classes.

To be Jewish, I was raised to believe, meant understanding oneself as a memberof a tribe that over and over had been cast out, mistreated, slaughtered.Millenniums of oppression that preceded it did not entitle us to a homeland ora right to self-defense that superseded anyone else's. If they offered usanything exceptional, it was a perspective on oppression and an obligation bornof the prophetic tradition: to act on behalf of the oppressed and to cry out atthe oppressor.

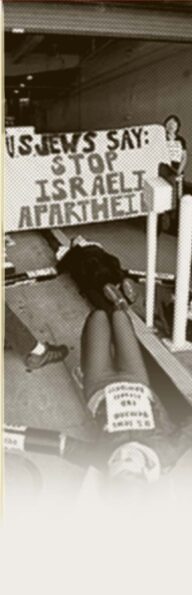

For the last several decades, though, it has been all but impossible to cry outagainst the Israeli state without being smeared as an anti-Semite, or worse. Toquestion not just Israel'sactions, but the Zionist tenets on which the state is founded, has for too longbeen regarded an almost unspeakable blasphemy.

Yet it is no longer possible to believe with an honest conscience that thedeplorable conditions in which Palestinians live and die in Gazaand the West Bank come as the result ofspecific policies, leaders or parties on either side of the impasse. Theproblem is fundamental: Founding a modern state on a single ethnic or religiousidentity in a territory that is ethnically and religiously diverse leadsinexorably either to politics of exclusion (think of the 139-square-mile prisoncamp that Gazahas become) or to wholesale ethnic cleansing. Put simply, the problem isZionism.

It has been argued that Zionism is an anachronism, a leftover ideology from theera of 19th century romantic nationalisms wedged uncomfortably into 21stcentury geopolitics. But Zionism is not merely outdated. Even before 1948, oneof its basic oversights was readily apparent: the presence of Palestinians in Palestine. That led someof the most prominent Jewish thinkers of the last century, many of themZionists, to balk at the idea of Jewish statehood. The Brit Shalom movement --founded in 1925 and supported at various times by Martin Buber, Hannah Arendtand Gershom Scholem -- argued for a secular, binational state in Palestine in which Jewsand Arabs would be accorded equal status. Their concerns were both moral andpragmatic. The establishment of a Jewish state, Buber feared, would mean"premeditated national suicide."

The fate Buber foresaw is upon us: a nation that has lived in a state of warfor decades, a quarter-million Arab citizens with second-class status and morethan 5 million Palestinians deprived of the most basic political and humanrights. If two decades ago comparisons to the South African apartheid systemfelt like hyperbole, they now feel charitable. The white South African regime,for all its crimes, never attacked the Bantustans with anything like thedestructive power Israelvisited on Gazain December and January, when nearly1,300 Palestinians were killed, one-third ofthem children.

Israeli policies have rendered the once apparently inevitable two-statesolution less and less feasible. Years of Israeli settlement construction inthe West Bank and East Jerusalem havemethodically diminished the viability of a Palestinian state. Israel's newprime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, has even refused to endorse the idea of anindependent Palestinian state, which suggests an immediate future of more ofthe same: more settlements, more punitive assaults.

All of this has led to a revival of the Brit Shalom idea of a single, secularbinational state in which Jews and Arabs have equal political rights. Theobstacles are, of course, enormous. They include not just a powerful Israeliattachment to the idea of an exclusively Jewish state, but its Palestiniananalogue: Hamas' ideal of Islamic rule. Both sides would have to find assurancethat their security was guaranteed. What precise shape such a state would take-- a strict, vote-by-vote democracy or a more complex federalist system --would involve years of painful negotiation, wiser leaders than now exist and anuncompromising commitment from the rest of the world, particularly from theUnited States.

Meanwhile, the characterization of anti-Zionism as an "epidemic" moredangerous than anti-Semitism reveals only the unsustainability of the positioninto which Israel'sapologists have been forced. Faced with international condemnation, they seekto limit the discourse, to erect walls that delineate what can and can't besaid.

It's not working. Opposing Zionism is neither anti-Semitic nor particularlyradical. It requires only that we take our own values seriously and no longer,as the book of Amos has it, "turn justice into wormwood and hurlrighteousness to the ground."

Establishing a secular, pluralist, democratic government in Israel and Palestinewould of course mean the abandonment of the Zionist dream. It might also meanthe only salvation for the Jewish ideals of justice that date back to Jeremiah.

Ben Ehrenreich is the author of the novel "The Suitors."